One of the Scribbler’s collateral ancestors, Daniel Gibbons, published “God in Us,’’ a brief book about “Quakerism,’’ in 1928. Gibbons worked as a journalist in New York and Philadelphia. In his youth, he attended Lampeter Quaker Meeting in Bird-in-Hand.

Near the end of that book, Gibbons lists among the church’s hopes for the future “to effect a permanent reconciliation between faith and culture whilst opening wide the door to the highest of both.’’

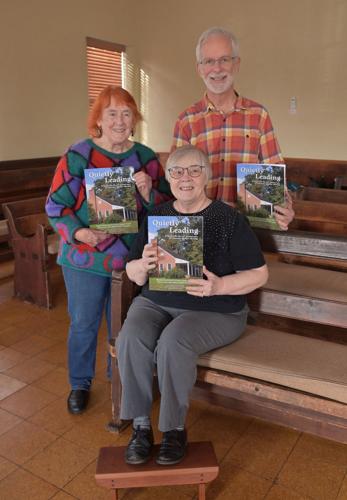

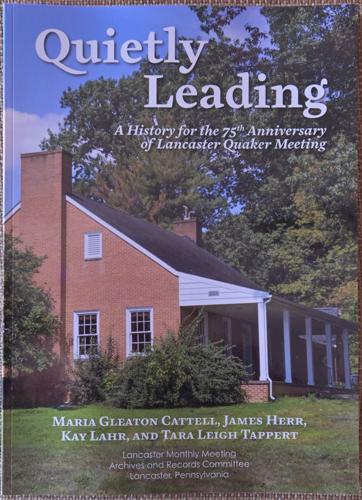

Lancaster’s Quaker Meeting is pursuing that ideal. The new book, “Quietly Leading: A history for the 75th Anniversary of Lancaster Quaker Meeting,’’ clearly illustrates that.

Founded in 1947 and worshiping for the first time in the meetinghouse on Tulane Terrace in Wheatland Hills in 1955, the church has served as a source of spiritual enlightenment as well as a home base for cultural and social activism in this community.

Among the early members of the congregation were Paul and Esther Whitely. Paul Whiteley, a Franklin & Marshall psychology professor, worked to improve race relations and offered advice to young Quakers about their responsibilities as conscientious objectors to the military draft.

As an early environmentalist, Frances Bear, of Martic Township, was one of the first landowners in the county to preserve her farm in perpetuity. She and other meeting members were active in starting what is now the Susquehanna Waldorf School in Marietta.

Robert Neuhauser, who managed the development of TV camera tubes at RCA, worked on multiple projects with the Friends Committee on National Legislation and the American Friends Service Committee.

Lancaster attorney Jean Kohr, working with the Susquehanna Valley Alliance, won two lawsuits concerning the damaged Three Mile Island nuclear reactor. The first required the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to keep the public informed about the 1979 accident at TMI. The second halted a plan to return treated radiation-contaminated water to the Susquehanna River.

That’s a small sample of individual and group responses to community and world challenges that church members have initiated during the past 75 years.

The book is not only a primer on how to promote positive social change, but also a guide to how to build a “new’’ Quaker church. The church needed a room full of benches and so gathered unneeded benches from five meetinghouses in Chester and Delaware counties. They now form a kind of museum of antique Quaker benches.

There was an earlier Quaker meeting house in Lancaster. What happened to it?

That meeting, established in 1753 just south of Lancaster’s Penn Square, on ground where Lancaster’s Salvation Army now operates, functioned for several decades. It was “laid down’’ in 1802.

The book suggests that one of the largest blows to that early congregation may have come when British troops “ransacked the meeting house’’ during the Revolutionary War.

That is possible. There was a more plausible documented attack on the Lancaster meetinghouse during the Revolution. It came from a mob of “patriot’’ vigilantes who targeted the place to intimidate its pacifist members.

The late Charles Holzinger, a member of Lancaster Friends Meeting, told the Scribbler that the meetinghouse’s minutes for July 1777 note that a company of “Paxton Militia’’ broke into the building, tore it apart and left it “entirely unfit for the purpose for which it was built ...’’

The current meetinghouse has a more placid but vibrant history, capably assembled in this book by Quaker authors Maria Cattell, James Herr, Kay Lahr and Tara Tappert. The book will be sold at LancasterHistory.

Jack Brubaker, retired from the LNP staff, writes “The Scribbler’’ column every Sunday. He welcomes comments and contributions at scribblerlnp@gmail.com.

![Scherenschnitte enlivens book on 19th century medical remedies [The Scribbler]](https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/lancasteronline.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/f/4c/f4cba204-e729-11ef-83ff-b7db2ab46ed9/67a91935d04ff.image.jpg?crop=1268%2C1039%2C3%2C0&resize=150%2C123&order=crop%2Cresize)

![Postlethwaite’s Tavern, Lancaster’s first courthouse, to be sold at auction [The Scribbler]](https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/lancasteronline.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/8/af/8af0d132-e58b-11ef-b458-17a5110babd5/67a661f094462.image.jpg?resize=150%2C103)

!['Shonkalay' and other unorthodox teaching strategies [The Scribbler]](jpg/67993f38a6f8c.image22a1.jpg)