Gil Delaney, the veteran Intelligencer Journal political reporter who retired in 2000, said interviewing President Jimmy Carter at the White House was one of the greatest highlights of his 32-year career in journalism.

Carter, who died Monday at 100, had two motivations when it came to inviting Delaney and two other central Pennsylvania reporters to interview him in April 1980 – the ongoing clean-up of the partial nuclear reactor meltdown at Three Mile Island, and a serious primary challenge from Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts.

Pennsylvania was critical to winning renomination and reelection in the fall, Delaney said. And showing his involvement in resolving the reactor mess was one way to court voters here without making a traditional campaign trip, which Carter had suspended while U.S. hostages continued to be held in Iran.

Throughout the reactor crisis, Carter pledged to prioritize public safety and to share accurate information, relying on his own background as an officer in the U.S. Navy’s nuclear submarine program.

Delaney, who now lives in Homestead Village Retirement Communities in Lancaster, said Carter kept those promises.

“He was always a force for decency,” Delaney said of the 39th president.

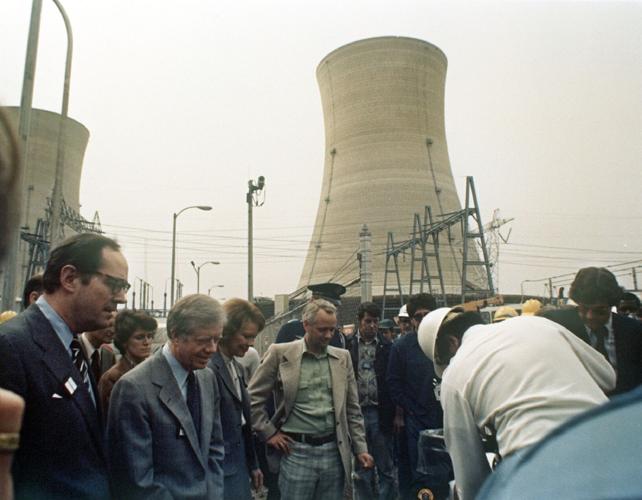

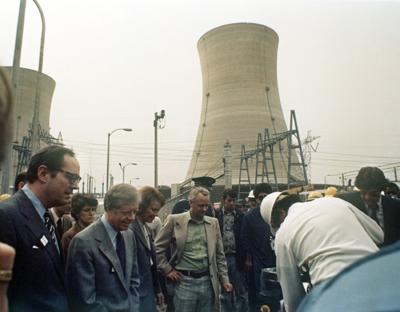

Carter’s visit to the reactor site on April 1, 1979, helped calm the worries and fears of people living near the power plant, according to Delaney, who had himself sent his family out of town after the incident.

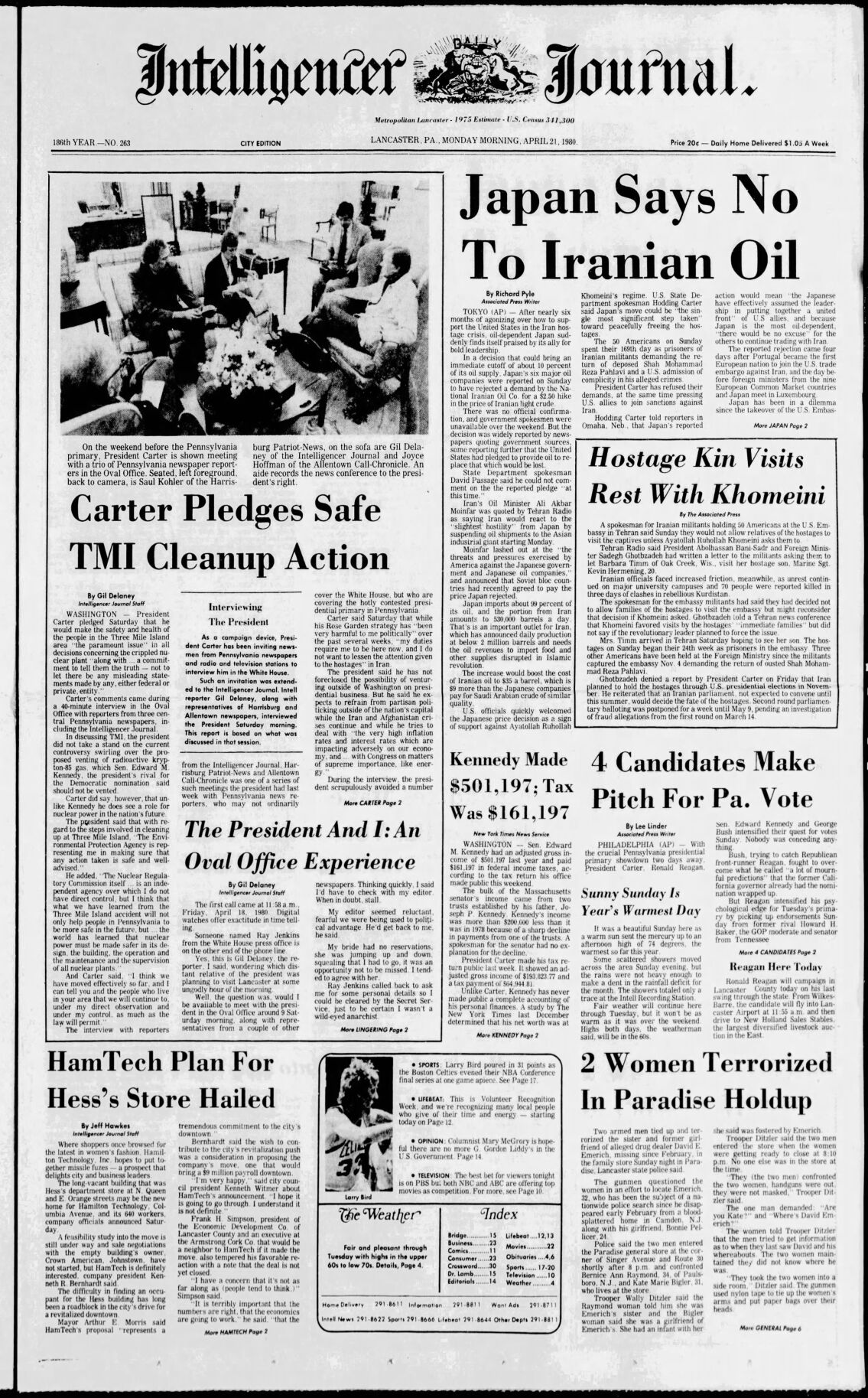

Gil Delaney's story about his interview with Jimmy Carter appeared on the Intelligencer Journal's front page on April 21, 1980.

Gil Delaney's story about his interview with Jimmy Carter appeared in the Intelligencer Journal on April 21, 1980.

The interview

Delaney received the offer to interview Carter at 11:58 a.m. on Friday, April 18, 1980, according to a column he wrote about the visit. He’d needed to be in Washington by 9 a.m. the next day to meet the president.

Before he could agree, Delaney had to convince his seemingly reluctant editor, who thought the interview could be a simple publicity stunt ahead of the upcoming presidential primary. After some back-and-forth dialogue, the pair agreed it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to interview the sitting president and that Delaney should go.

Delaney said he spoke to many reporters in the newsroom and people in his personal life to seek their input about what he should ask Carter.

Carter, according to Delaney, had initially wanted a reporter from the Sunday News – not the Intell – for the interview to benefit from a wider audience (at the time, the Intell had about a third the number of subscribers as the Sunday paper). But members of Lancaster County’s Democratic Party had convinced the president’s staff that Delaney was the right fit.

The interview in the Oval Office lasted 37 minutes and 17.9 seconds, according to the stopwatch function on the wristwatch Delaney used to time it. Questions asked by Delaney and the other journalists ranged from the economy to Iran (the U.S. embassy staff had been taken hostage five months prior), Afghanistan (recently invaded by the Soviet Union) and, of course, politics.

Three Mile Island, as “the elephant in the room,” was also addressed, Delaney said.

He recalled Carter wearing a sweater and appearing tired.

A full transcript of the interview was shared with the Washington press corps by noon that Saturday, Delaney said. But due to the Intell’s deadline and print schedule, his stories didn’t run until the following Monday.

By then, many other outlets had beaten Delaney to publish stories about Carter’s comments. Despite the “frustrating” outcome, Delaney still looks back fondly at the interview.

“Certainly, that was one of the highlights of my career,” Delaney said.

‘Marvelous legacy’

Delaney said Carter’s “underappreciated” yet “marvelous legacy” extends beyond his handling of the Three Mile Island accident. As an example, he pointed to Carter’s “stroke of genius” negotiation of a peace deal between Egypt and Israel.

His brokering of that deal and his wide-ranging work post-presidency alongside his wife Rosalynn established their reputation as global humanitarians.

“Carter was a master at small ball politics,” Delaney said. “He could come across as knowledgeable and relatable, but he wasn’t necessarily someone who could give a stemwinder speech that rallied the crowd. He was very low-key.”

That shortcoming was one reason Carter lost the presidency six months after that interview, Delaney said.

He called Carter’s Republican opponent in the 1980 general election, Ronald Reagan, the “master of the media.”

![School boards, mayors and more: What to watch for in Lancaster County's 2025 municipal elections [analysis]](https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/lancasteronline.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/c/67/c676004d-2cd8-5bb4-a120-c43c3339fd6c/524dc13d211fb.image.jpg?resize=150%2C108)