Teams of door knockers. Billboards galore. Ads in local print publications. And free rides to the polls on Election Day.

The Republican Party and its allies are toiling to court Lancaster County’s potential Amish voters, as they seem to do every year.

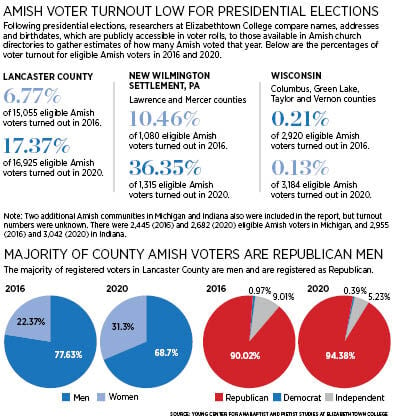

Researchers remain skeptical about the impact those efforts will have, as less than 1 in 5 eligible Amish voters in Lancaster County usually turn out at the polls, according to data from Elizabethtown College.

Yet Republicans in Pennsylvania, where the margins of the past two presidential elections have been razor thin, continue a no-stone-unturned approach to encouraging the Amish vote.

Scott Presler, a political organizer who led some “stop the steal” efforts in 2020, has led much of the GOP’s ground game. His outreach organization, Early Vote Action, has staffed a near-weekly table at the Green Dragon Market in Ephrata Township and Root’s Country Market & Auction in East Hempfield Township to reach potential Amish voters.

Scott Presler, a political organizer who led some “stop the steal” efforts in 2020, (right) poses with Lancaster County Commissioner Josh Parsons (left) outside of the county Board of Elections office on Oct. 29, 2024.

Standing outside the Lancaster County Board of Elections office on Oct. 29, Presler claimed the number of Amish he’s helped register to vote this year is “in the thousands,” but he would not elaborate.

Presler’s imprecision, coupled with online misinformation about the number of eligible Amish voters, leads Steven Nolt, a professor of history and Anabaptist studies at Elizabethtown College, to think some Republicans are overpromising about delivering a sizable Amish vote.

“Every vote counts. I’m not trying to diminish that,” Nolt said, but he noted the number of Amish who are eligible to vote is fewer than 45,000 in Pennsylvania, and they vote in small numbers. He’s seen claims online that falsely overestimate the amount eligible by up to four times.

Ryan Sexton, a Columbia GOP committeeman working with Presler, points to the fact that former President Donald Trump lost Pennsylvania in 2020 by only about 80,000 votes. Any amount of Amish votes could help Republican candidates gain an advantage this year, he said.

Other local volunteers for the Republican Party said they, too, have seen enthusiasm to vote this year among potential Amish voters.

During his Sunday rally at Lancaster Airport, Trump called out to the Amish supporters he thought might be in the crowd. When he saw none, the audience shouted back at him

“They’re at church,” Trump responded, repeating what someone shouted to him. “I love that.”

READ: 7 things to watch on Election day in Lancaster County

Amish turnout

In 2020, just 2,900 of the estimated 17,000 eligible Amish voters in Lancaster County cast a ballot, according to data from the Elizabethtown College researchers. Those numbers were smaller in 2016, when Trump first ran for the White House, at just 1,000 of 15,000.

Among the Amish who voted, more than 90% were registered with the Republican Party. Less than 1% were registered with the Democratic Party, and the remainder were unaffiliated voters. That disparity between party registrations is why some Pennsylvania Republicans view the Amish as an untapped stockpile of earnable votes in the key swing state.

David Lapp, a former member of the Amish community and CEO of local food nonprofit Blessings of Hope, said it’s a misconception that Amish oppose voting.

“I think it’s more of a mindset,” Lapp said. “I think they want to be more passive and not get involved.”

Though he’s not involved in voter outreach efforts, Lapp said this year there are “definitely some people that are registering to vote that would not have otherwise” due to recent get-out-the-vote efforts. He said he hopes the attempts to boost Amish voter turnout are effective.

Driving Lapp’s vote toward Trump this year has been the increased cost of living and the “overall leadership of the country.” He said both were in better standing when the Republican Party held the White House.

Nolt said little reliable data exists to show trends in Amish political attitudes and activities. To gather statistics on Amish voter turnout, Nolt’s team compares names, addresses and birthdays publicly available through voter roles to Amish church directories. He said it’s a time-consuming process.

Nolt won’t have this year’s turnout statistics until sometime in 2026.

For registered voters in the Amish community, Liesa Burwell-Perry of The Encounter church in Bainbridge is organizing a fleet of volunteers to provide free transportation to their local polling places. The group has posted flyers around the county listing a number to call for a ride to and from the polls.

READ: The ins and outs of polling places on Election Day

‘Increased awareness’

David Nissley, a conservative who led an unsuccessful GOP primary campaign for a state House district seat in the county’s southern end this year, said he’s been out canvassing Amish homes for the Trump campaign this fall. Nissley was raised in an Anabaptist church.

Driving the Amish vote, he said, are concerns about the economy and the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“They have a general distrust of government that is deep and cultural, and events like COVID were very significant in their perception that that mistrust is well-placed,” Nissley said.

He said Amish voters are also concerned the Democratic Party could threaten their conscientious objector status and private schools, as well as implement further regulations on their farms’ zoning permits and stormwater management systems.

Nolt said it’s hard to believe that “sort of fear approach” will stir turnout this year. The most effective outreach efforts, he said, tend to be “ground-up” approaches where outreach coordinators focus on local issues and local candidates.

“If Amish people are getting involved and interested in politics, it’s going to be through these local relationships,” Nolt said.

Lancaster County Congressman Lloyd Smucker was born into an Amish family, though they left the order when he was 5 years old. Smucker said in a statement to LNP | LancasterOnline that his campaign has hosted three in-person events and has “invested in programming” to boost mail-in voting among the Amish.

“Lancaster County is home to the largest population of Amish in Pennsylvania, and it’s important that we engage with the community in the legislative and political processes,” Smucker said. “From my conversations with the community, there is an excitement to vote this year and an increased awareness that every vote cast can make a difference.”

READ: Voter turnout could be the deciding factor on Election Day, latest F&M poll finds

Outside spending

No matter how focused they may be, Nolt said billboards may be the least effective vote-getting method.

Some billboards around the county read, “Pray For God’s Mercy For Our Nation” and depict a straw hat with “VOTE” written in white on its black ribbon. That image sits over the words “PROTECT OUR FREEDOMS.”

Those signs list a phone number leading to the Pennsylvania Department of State voter registration line and name Fer Die Amische as their funding group. Fer Die Amische is not registered as a political action committee with the Lancaster County Board of Elections, Department of State or Federal Election Commission.

Emails sent to the address listed on the sign seeking comment went unreturned.

Another group, Concerned Americans for America, has paid for separate billboards around the county saying “AMISH for TRUMP.” One can be seen on New Holland Pike near Freeze & Frizz Drive-In in Upper Leacock Township.

Concerned Americans for America is a Florida-based super PAC that has spent more than $500,000 during this two-year election cycle in support of the Trump campaign, according to OpenSecrets.org. Committee officials did not respond to a request for comment.

Over the course of every presidential and midterm election since 2016, a separate group called Amish PAC spent nearly $500,000 total to reach Amish voters in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

This year, as of Sept. 30, the group had spent nearly $18,000 nationwide. The group’s ads have appeared in local print publications including the Advertiser, Pennysaver and Lancaster Farming.

One ad this year — addressed, “Dear Brother or Sister in Christ” — depicted a farmer and two children tending to a wheat field using a horse-drawn hay baler. The text of the ad equated not voting to inaction, a sentiment Nolt called “quite un-Amish.”

“In traditional Amish theology,” he said, “the choice is not between voting, on the one hand, and inaction on the other. It is between the church acting as the church, and church people being tempted into diverting their energy into worldly action that is not the church’s calling.”